Below are the remarks offered by David Epstein, Jeff Potter, Emily Todd, and Todd Sumner at Saturday’s event in honor of Eric Grinnell.

David Epstein ’87, Chair of the Board of Trustees

Good afternoon. Thank you for joining us on this beautiful day to celebrate Eric Grinnell’s life.

Frankly, I am at a loss for words to honor Mr. Grinnell…. but I do know Eric was a very special person and he has touched all our lives. It is wonderful that we can all be together to share our stories and memories of our teacher and our friend.

I would imagine that we are all drawn here today so that we can each, in our own way, say: Thank you, Eric.

As Mark said, my name is David Epstein – I started at the Academy as a 9th grader in 1983, and I now serve as chair of The Academy at Charlemont’s Board of Trustees.

Depending on how long you have known me, that may sound a little odd. You see I was not what you’d call a “model student” – at least not academically – but that did not matter to Eric Grinnell. He always treated me like a young adult, never spoke down to me or to any of us. He always made us feel very special. In fact, Eric entered into a compact of respect with everyone he knew; he insisted on his own dignity, but also ours.

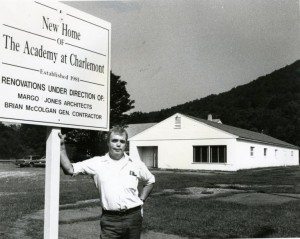

Believing deeply in the benefits of a classical education, Mr. Grinnell, his wife and colleague Dianne Grinnell, and four other hardy souls, founded The Academy in 1981.

The doors of the school opened in the fall of that year with twenty-four students, a small group of dedicated teachers, and one headmaster gifted with tremendous intellect, charm and determination.

And not just any school, but an Academy based loosely on Plato’s school of philosophy in ancient Greece, except instead of young Athenians it was to be populated by the miscellaneous offspring of sturdy Yankee farmers and artsy flower children. That took real faith and brains! It was very BOLD and kind of crazy. What an entrepreneur!

In The Academy at Charlemont, Eric Grinnell created a warm and welcoming place dedicated to nurturing in students a passionate appreciation of knowledge and art, the habit of critical thinking, delight in the precision and beauty of language, and commitment to the principles of a just society expressed in a tradition of service.

These elements reflected his own values and passions, and thirty-three years later, they continue to be at the heart of the school’s identity.

A fellow alumni, Ian Gillingham, said in a recent e-mail: “Those of us who were at The Academy in the early days remember what a dignified and inspiring presence Eric was. The school, lodged in a borrowed schoolhouse in Charlemont center, could scarcely have had more humble beginnings, but Eric brought ceremony and high purpose to those modest surroundings.”

I remember a conversation with Mr. Grinnell on Mountain Day, 1984 or 1985. As we walked along, I asked him what he imagined The Academy would look like in 10 or 20 years. I don’t recall how we came to that point, but I do remember that that he described a small campus cut into a hillside. As he spoke I pictured a modern day Machu Picchu. (Which may give you some idea of Eric’s gift for inspiring lofty ideas in young minds).

Mr. Grinnell served as Headmaster for over twenty years, retiring in 2002. His devotion to the school and his students was generous, personal and exceptional. For many years he and Dianne lived on one salary in order to assure that others would be paid and that a fragile school could survive and grow.

And the small school – his school – our school – survived and thrived. Today The Academy has over 350 graduates and an additional 300 who called this their school at some point on their educational journey – people of talent and accomplishment; creative, smart, engaged, and productive – we are, in part, the people Eric saw in us and the people he helped us become. Even now, and into the future, each class, every student, enjoys the benefit of his vision, his intelligence and his care. His legacy is wide and deep and very personal. We have all been blessed by the light of his life.

And, so, today, on behalf of the Academy Trustees and personally, I am here to say one more time: “Thank you, Mr. Grinnell.”

Jeff Potter ’84

I don’t know about other Academy alumni, but in me there’s still a little bit of the 14-year-old wide-eyed sophomore who walked through the doors of the old Charlemont High School building on September 14, 1981.

That part of me has a hard time truly perceiving Eric Grinnell as gone. To me, he was larger than life. If I didn’t see him as immortal, I had certainly imagined that he would have been struck down by a thunderbolt.

There are many of us here, and we have many opportunities to share wonderful Eric Grinnell stories. Or, as many of us would still say, “Mr. Grinnell” stories. (When I was in college, Eric and Dianne made it very clear that they wanted to be on a first-name basis, but I couldn’t do it. The conversion of the four-syllable mis-ter-grin-nell just didn’t translate — how could he be anything BUT Mister Grinnell? Finally, one day in 1987, I referenced “Mister Grinnell,” and Dianne grabbed me by the lapels and said, “ER. RIC.” It stuck.)

So we’ll hear a lot of anecdotes — including many, I’m sure, from Todd and from Emily. I’d like to avoid excessive nostalgia and — at least mostly — step back and think about this extraordinary man, teacher, mentor, friend, and the lessons that he — knowingly or unknowingly — left behind.

1. Make it up as you go along.

The day The Academy opened, we started the morning with Eric — in his three-piece suit, of course — addressing the school community, conveying nothing less than full confidence. To our young minds, our tiny school ran like a well-oiled machine. I look back — having started enterprises of my own — and wonder, HOW DID THAT HAPPEN?

I remember that first Friday, Eric opened our first school meeting with an aside. “It feels like we’ve been doing this for years,” he said.

That’s because he — with ample help from his colleagues, but we all know that he was a ringleader — made it up as he went along and instilled enough confidence that we didn’t even think twice about coming along, and together we made it all work. By every logical measure — few students, no money, a crumbling building that guzzled fuel oil — The Academy at Charlemont should have been a fiasco.

2. Live your life with honor.

How many of us really knew, internalized, the word “honor” before we were students? Even in the years before The Academy’s Honor Code was fully formalized — I was in college by the time that happened — I can tell you that the concept of living and working with honesty and integrity came to mean something to me.

3. Don’t do the easy thing, do the right thing.

In starting this school, most of its founders gave up secure, tenured teaching careers in the public sector because young people in this area deserved something so much better that it required a wholesale re-imagination of their educational environment — a whole new school.

4. Be a gentleman. (That’s “man” as in “humankind.”)

One spring afternoon, we were pasting up The Grove, and somehow we began discussing the topic of what exactly defines a gentleman. David McKay, one of the founders of the school and who, with Pat, was our yearbook advisor, said, “I think Eric Grinnell is the definition of a perfect gentleman, whether he’s dressed in a suit or in blue jeans covered with dirt from the garden. He can hold a civilized conversation with anyone, regardless of the topic, their education, and who they are.”

Especially in a polarized political environment where it sometimes seems as if people just aren’t willing to listen to or acknowledge the very humanity of others who hold different views, doesn’t that distill, in a nutshell, everything we should all aspire to be, the best way that we all can live our lives?

It’s so simple, but it’s so beautiful. What a great lesson.

5. Don’t do it for the money.

Maybe I’ve taken this lesson to an extreme.

6. Enjoy the finer things, and the good people, in your life.

Eric and Dianne, and their colleagues, worked damned hard. They also enjoyed themselves immensely, “living la dolce vita in Heath,” as a mutual friend once said, tongue in cheek. It was an HONOR (there’s that word again) to be invited to their house for senior dinner. The various subsequent get-togethers I’ve enjoyed there over the years have always emphasized good food, good drink, good company.

I will never forget volunteering to work on the Vox newsletter when I was in college and being invited to Heath on that cold winter evening, an impromptu gourmet meal for multiple Academy folks and a roaring fire on the hearth. A highlight of the evening was when Dianne insisted that Eric model a Turkish robe that he acquired on one of their many overseas travels. I think of Eric, a good sport, coming downstairs in this flowing, richly colored regalia, perfectly deadpan with trains of lush fabric in his wake. He, of course, said something dry and witty.

7. Find your life’s work.

Any of us who ever had Eric as a teacher knows that he didn’t work as a teacher, he WAS a teacher.

In those early years, it was clear that he often taught our Latin class without any preparation or planning whatsoever. And the thing was, he didn’t have to — he was that good.

He would flip the textbook open, remind himself where we had left off the previous day, and out would flow this fully-realized, fully-formed lesson. It was like watching an accomplished jazz musician.

Did any of us ever doubt that this school was his life’s work?

8. Create community.

Eric envisioned a cohesive and functional school community, fully realized by the New England Town Meeting as a framework. For so many of us, this community was broken and missing from our academic experience. For so many of us, we’ve carried into our own lives and livelihoods the value of community that Eric imparted to us and to this school.

9. Keep learning.

Eric lived the example that the pursuit of knowledge was a lifelong endeavor. What more do we need to say?

10. Embrace your eccentricities as a badge of honor, and have fun with them.

When Eric discovered the Internet in the mid-90s, he told me that he had joined a Listserv, which lets members with a mutual interest send emails to an entire group and have a conversation en masse. I have to say, his embrace of such hardcore Internet geekery took me by surprise.

Then he told me about the Listserv. Its list members wrote exclusively to one another about pretty much anything.

In Latin.

Eric didn’t just believe Latin was a vital part of this secondary-school foreign language curriculum. He also LOVED it, and his love for dead languages and classical antiquity was part of his very being.

How many of us here remember Eric teaching us how to sing “Jingle Bells” in Latin? How completely INTO IT he would be? “OOOOOOOOO tantum est gaudium…” And making us laugh at the absurdity of the translation back into English: “OOOOOOO, how great is joy to ride in sled.”

He didn’t just go through the motions… he was all in.

And this difference highlights what I think is the most important lesson that he imparted to us.

We can all list so many Eric Grinnell eccentricities. The pince-nez. The watch fob. The pronunciation of “issues.” The gas lights in their house. The antique gadgets. The opera. The use of the subjunctive mood in casual conversation. The quill-pen-flourishes signature. And, of course, the Latin.

Eric embraced his eccentricities. He made them his own, part of his DNA. He was his own man. He went through life, the perfect gentleman, giving us an education and an illustration of how to live life as good, honorable people, as engaged and civic-minded citizens, as creative thinkers and visionaries who aren’t afraid of changing the status quo.

He didn’t bludgeon anyone with his high standards and esoteric interests. He made it seem easy, natural, right.

And because so much of this service is, rightfully, devoted to Eric’s favorite beloved serious music-with-a-capital-M, I would like to invite all Academy alumni to join in with a quick verse dedicated to the wisdom and the sheer pluck and joy of what Eric gave to us, to this school, to his community, and especially to Dianne.

Oh, how great was his joy.

Tinnitus, tinnitus, semper tinnitus

o tantum est gaudium

quil mi-hi in tra-ha.

Emily Todd ‘85

I first met Mr. and Mrs. Grinnell—or Eric and Dianne, as I now should call them—at my admissions interview. It was late spring in 1981, and the interview—or meeting, I am actually not sure what it was!—took place at a neighbor’s home in Plainfield. I was 13 and a student at a private girls’ school in Boston but my family was planning to move to Ashfield. Eric and Dianne, I now realize, were young too, in their early 40s. They and the other founders had an idea to start a school; my family needed a school for me.

It was a weekend day, deep in mud season, and it might have been one of the few times—apart from Mountain Day—that I ever saw Eric wearing jeans. I remember that we sat on the neighbor’s couch, and I answered questions about my current studies and interests. Mr. Grinnell then presented us a school. He gave me a three-fold pamphlet (on cream color paper,with maroon type), outlining a course of study that included Latin, French, Humanities, Science, Math. We were sold on the school, which was really just a bold idea—I am not sure there was even a building secured. Eric was so persuasive that I can’t remember ever debating whether I would attend. It seems like after that meeting I was an Academy student.

The school collected students during the late spring and summer of 1981—David Rees, Dane Boryta, Peter Gowdy, Wes Rosner, Karen Parmett, Becky Bluh, Jeff Potter, Ginny Gabert, Laurie Wheeler, and others. I remember learning their names every week and then later every couple of days as September approached, when we were finally up to 24 students in seven grades. All of us found our way, for different reasons, to this place that our families, I imagine, saw as creating some new possibility for our young lives. We showed up to our new school, an abandoned school building in the center of Charlemont, in late August to move desks out of the basement and to do other tasks around the place, and then on a day in September we gathered in the Common Room to begin being a school. The story I heard from the beginning was that the founders — Eric and Dianne Grinnell, Pat and David McKay, Maggie Carlson, and Lucille Joy — were responding to the budget cuts in the public school system brought about by the passage of Proposition 2 1/2 and wanted to create a school in which the arts and a classical education were preserved. As a student on that first day, I remember thinking that we were embarking on a noble project: we were going to uphold a threatened tradition.

Like Jeff, I want to reflect on what I think we learned from Eric during these first four years at The Academy and on what legacy he left for us.

Eric Grinnell modeled for us boldness and adventure. My old friend Dane Boryta, who’s running a restaurant in San Francisco these days, remembers Eric as “fearless, driven, inspirational.” As an adult, now the age that the founders were when they established the school, I more fully appreciate the risk they took: not knowing really how to make ends meet or whether things would work out for them or the school. But as teenagers we benefited from the sense of adventure at the beginning. The Academy in its early days made all of us step up—we had to play soccer in order for the school to field a team, we had to join the yearbook staff if we wanted there to be a yearbook, and, in my case, I had to show up for Latin class because I was the Latin class. The Academy taught us to come forward and make things happen. This is a theme we hear today: Eric knew how to invite people along in what was admittedly a risk-taking enterprise and to help them to believe in it.

And the inherent riskiness of the undertaking was always, in fact, tempered by some tone of certainty. Mr. Grinnell made sure that we started to see ourselves in history, as building on a past. We established tradition, with our school colors (I still have my Academy at Charlemont jacket and T-shirt from the first or second year) and the Honor Code and Roman Feasts. Mr. Grinnell infused dignity and reverence for intellectual tradition in all that he did with us. I saw my first opera because of Eric, went to the Cloisters, learned to identify a Brandenburg concerto, translated Virgil, read Dostoevsky and Sartre and Tolstoy and Hardy and Dickens and Fitzgerald. He made us feel that we had a strong foundation, that we were operating in a great tradition, even though our school was months old in a borrowed building.

I remember Mr. Grinnell at Morning Meeting leaning forward on one of the Common Room tables, leaning forward and speaking in a booming voice. Sometimes it was a playful voice, sometimes it was stern, but he was representing what we should do and what we should be during the day and week ahead. Eric’s sense of an intellectual tradition and his vision to have us create our own tradition guided us; he was going to point us in the right direction, at the beginning of every day.

Finally, I remember the example Eric set as an educator. Before the field of education had started talking about interdisciplinarity, project-based learning, civic engagement, life-long learning (terms I hear now all the time in my work in higher education), Eric was taking those very approaches at The Academy. He helped to design a rigorous humanities curriculum that culminated in the Humanities seminar, he brought us out to study one-room school houses in Heath as part of an extensive local history project, he insisted on integrity, and he showcased is own “life-long” learning through his erudition and the speakers he brought to school. As my friend Donald Braman recalled in an email to me this week, “Mr. Grinnell trusted and expected a lot from everyone, which made me feel like I was actually doing something that mattered.” So that’s the quality I saw him model as a teacher: he helped students to produce knowledge, not be consumers of it, and above all he emphasized the importance of making connections—to ideas, to communities, to each other.

At my graduation in 1985, I quoted Kurt Vonnegut, “You are what you pretend to be,” pointing out that “we pretended to be a school, and we became one.” Eric came up to my mother afterward, and said, “Emmy’s right: the realest thing in the room that first morning of the school was the donuts.” But, you see, I never felt that we weren’t real, and I think a seriousness of purpose informed the school because we were not only becoming a school but the school was also helping us to become ourselves.

Here’s the thing, though: I don’t remember Eric giving advice. I don’t find myself quoting Eric or remembering phrases that guide my life. But I do remember what he modeled through helping to establish the school and helping us to be part of the school, and I would say that his example is his most important legacy. Albert Schweitzer says, “Example is not the most important thing in influencing others. It is the only thing.” So now I find myself as an adult, mostly in awe that someone my age would take such a chance but grateful he did, and even if I can’t claim to be as bold, I must say that getting involved in my community, stepping up to establish something new—that’s in my bones now, I learned how to do that because of Mr. Grinnell. I am old enough now to realize the gift of having read so widely when I was young—so that I can understand things in new ways as an adult. And I see the value of making connections—and realize how lucky I am that I got the chance to do that when I was young, which has made it so much easier to forge meaning as an adult.

And I imagine all of our lives are richer—civically richer, artistically richer, intellectually richer—because of Eric’s example. His legacy is here in this room, in this building, in this community, and it is with all of us, in the lives we lead far from here. We are better prepared not only because of what he taught us in European History or Latin IV, but because of what he exemplified for us, as he used his own life to create something grand but also rooted in place and community. Even though he had only a flimsy pamphlet to show me 32 years ago, he brought The Academy to life for my family and me on that spring day in 1981, and here it is now a very real place, an institution shaped by values Eric embodied, values that will live on always through the lives of The Academy’s students.

Thank you.

Todd Sumner, former Head of School

Once upon a time there was a Princeton undergraduate who owned a horse-drawn carriage, a Brewsterbrougham that was already seventy years old when he bought it. At weekends and on spring evenings, he would harness his horse, Sam, to the carriage and, for a fee, drive fellow undergrads and their dates through the woodsy lanes and byways of Princeton. In this way he earned some spending money, provided a needed service to courting couples, made a reputation for himself on campus, and indulged his enthusiasm for elegant, horse-drawn vehicles. His entrepreneurship and showmanship—he was, of course, dressed for the part—landed him on the cover of the Princeton Alumni Weekly and, because of an incident I’m about to relate, in the New York Times and on the cover of Life Magazine. En route from Princeton to his family’s home in Rye, Eric drove Sam and the carriage across the Tappan Zee Bridge at four miles per hour, the traffic piling up behind him as bewildered drivers tried to make sense of what they were seeing. Could that really be a horse and carriage up there? When the trooper pulled him over and cited him for doing four in a forty minimum, Eric remembered saying “it doesn’t say anywhere that I can’t do this: this is a well maintained carriage and a well-trained horse; we’re traveling a public way…”

“It doesn’t say I can’t do this” might become a refrain this afternoon if we let it. Eric’s life was both ordinary and extraordinary, but it was remarkably consistent in that he never let convention stand in the way of an adventure, a good idea, or a vivid expression of who he understood himself to be. I chose this anecdote because it took place before most of us knew Eric—he was only nineteen at the time—but one can already recognize the Eric we all knew and loved: his sense of entitlement, his theatricality and sense of style, his enthusiasm, his appreciation of pre-industrial technologies and preservationist inclinations, his charisma—all of these are in evidence in this story. He would spend the next decade, roughly, figuring out how to be an adult in the world and still be true to himself. He worked and lived in Manhattan, buying and selling antiquities by day, enjoying the company of friends by night. He went to the opera. He joined the national guard. He traveled abroad. He gave dinner parties. He made life-long friends. He figured stuff out. In that way—needing his twenties to figure stuff out—Eric was quite ordinary.

Among the things he figured out were that he didn’t want to live in the city forever. Even though he had traveled the world, Eric made Heath his home and embraced stewardship of the Tucker Hill homestead when he bought the house and land from Arthur Cook. There are few left in Heath who could do a before-and-after comparison without photos, but let’s just say there was a lot of work to be done around the place when Eric came to town. Mr. Cook taught him to sugar, how to mix the gas for the gaslights, how to build and tend the fires. Eric enlisted the help and expertise of friends and neighbors over many years in the work of renovation, restoration, and rejuvenation. One might think of Tucker Hill Farm as a kind of rehearsal for launching The Academy, drawing as it did on Eric’s ability to motivate others to become part of something bigger than themselves. Plus, he knew how to make it fun. Dianne said the other day, “best I can tell they’d work all day and party all night.” That sounds about right.

By the time I met him, Eric had already found his vocation as a teacher of Latin, history, and contemporary issues—O Tempora, O Mores!. When I studied with him at Mohawk—and I see other Mohawk students here today—I appreciated his ready wit and his use of anecdote as he made the classical world or American history come alive. Later on, when we became colleagues at The Academy, I came to admire Eric’s ability to articulate the ideas that animated his teaching practice: developing critical thinking skills, honing one’s ability to present and persuade, fostering a commitment to the common good, and delighting in the play of ideas for their own sakes. These are, of course, the cornerstones of the liberal arts tradition and throughout his career as an educator Eric saw himself both as a champion of that tradition and as an innovator within it.

The Academy at Charlemont was, of course, his signature innovation, a school born of the good ideas of its founders and their ability—collectively and individually—to motivate others in pursuit of those good ideas. I think it would be hard to understand Eric’s motives in founding The Academy without first understanding how deeply his experience of Heath shaped his view of schools and schooling. Eric contributed to and helped to shape the town he loved, but it’s also true that Eric learned a lot from his neighbors, from the routines and rhythms and rituals of rural life, and from the disciplines of democratic governance in a town meeting polity. Social tolerance, entrepreneurial initiative, generosity in the face of need, hard work and sustained effort—all of these were valued in the Heath Eric encountered in the 70’s, but few institutions captured his imagination as an educator quite as much as town meeting: he loved to tell stories about exchanges he’d witnessed, debates he’d participated in, tactical moves he admired and detested. Eric’s commitment to citizen self-government and his admiration for the New England town meeting were foundational to The Academy, its program, and its mores.

Emily and Jeff have already spoken of the founding era and of Eric’s effect on them and the school they helped pioneer. I do know that none of us would be sitting in this space today were it not for Eric’s vision and effort over more than twenty years. Eric’s heroic and Stoic commitment to The Academy would not have been possible without Dianne, his co-founder, best friend, and partner in life. They came together in mid-life, having had other relationships and having come to know themselves. They shared a love of travel and together they explored the classical world, central Europe, Mexico, China, Cambodia, the Carribean, and much of the United States: Paris, Prague, and Palenque; London, Lisbon, and Luxor; Ankara, Angkor Wat, and Athens. They made two transatlantic crossings under sail aboard the Sea Cloud, a four-masted barque built for an American heiress. At home they cooked and cleaned and collected; they laughed and loved and lost; they welcomed friends, family, and stray animals to their hearth. They collaborated in the work of transforming Tucker Hill Farm into a comfortably elegant home, surrounded by flower gardens and pastures and lawns; their home was both a labor of love, a source of pride, and the center of their sociability. Eric’s pleasures were adult pleasures—cocktails and conversation, cuisine and connoisseurship—and in that way too he and Dianne were well matched.

Even though Eric’s life was in so many ways remarkable, his falling in love with a younger woman is less so. It may have been love at first listen, but his admiration for Renee Fleming grew exponentially and vibrantly: he referred to the lyric soprano simply as “Herself.” Not only did she build her reputation on the operatic literature Eric loved best—Mozart and Strauss—but she also arrived on the scene when Eric was, with Dianne, in a position to take a Saturday matinee subscription at the Met and see her perform there. Students from the early days of The Academy can recall trips to the Met to see Madame Butterfly, among other productions, taking backstage tours, and enjoying lunch at the Opera Guild. Eric’s love of opera was something that everyone knew about him, but not everyone knows that his parents were musicians: his mother was a professional singer and interpreter of the American songbook; his father played saxophone in Ellington bands well into his eighth decade. Eric was never a performer of music, but he helped make music happen wherever he went: at Mohawk he helped launch the annual musical theater productions; he helped Arnie and Ruth Black and those who love chamber music sustain the Mohawk Trail Concerts series; because they were so important in his own life, he made sure that music and the arts were integral to The Academy and a student’s experience here.

I have been trying to connect the dots this afternoon, to trace some through-lines and themes in Eric’s life and to lift up the key elements of his legacy. What I fear might have been lost is how much fun he was. He had a great capacity for connection, for wonder, and for laughter; he was compassionate, curious about the world, and deeply thoughtful. He helped those around him see what was possible—how their own gifts might be developed, how a community might be sustained, how a wrong could be righted—and motivated them to act, to move toward the possible. And he could draw on so many examples as analogies: he could conjure Perikles at the rostrum, Cicero in the Senate, Leonardo in his studio, Jefferson in his study, Lincoln at Gettysburg. He made it look easy. He used to tell of his grandmother—called Boo—who lived to be 102, sharing with him an early memory of being lifted on to adult shoulders in April 1865 to catch a glimpse of Lincoln’s funeral train passing through Columbus, Ohio. In two clicks we’re intimately connected, through Eric, to the American Civil War and Abraham Lincoln and the operatic struggle for equality. And even though Eric did not live quite long enough to hear the President of the United States alliterate Seneca Falls and Selma and Stonewall, he understood his own life and work to be part of something grand—the long good fight for dignity, decency, and democracy that has animated Western humanism for centuries.

With that, let us now enjoy some more of the music Eric loved best.

A Toast by Fred Cowan

Ad Lib.

I want to reaffirm your memories of Eric.

Some details may slide but in sum the essence of your memory is True. .. as in True North.

And in his 40 year friendship with us and his relations with others, Eric was faithful.

Many times he willingly did without, to honor a promise.

And, on a more personal note, he willed us to develop an appreciation of opera, the esthetic and practical benefit of lamp and candle light, and he assured us, faithfully, that champagne is suitable for all occasions.

That determination, strengthened perhaps, from his time on a beach in the Caribbean when he discovered that Veuve Cliquot could be had for $7.00 a bottle.

So. With his zest for life and his sense of fun recalled; his expressions and his quick step restored, I ask you now to join me in a toast to the man, memory, and the extraordinary legacy of Eric Ayres Grinnell.